Like Atari and to some extent Strategy First, Majesco is a publisher facing considerable financial issues. Its suits signed a long-term Steam contract last month as part of a refocus on low-investment and low-risk games: a goal that only a few short years ago would have meant bargain-bin shmups, but with today’s digital distribution systems and the forthcoming Nintendo Wii can and has lead to a more progressive path. Which is great, but for whom?

Majesco’s Steam venture is going to be successful–how could it not be? But that success will be for Majesco. For their sub-contracted developers and others in the same situation, Steam in fact means even less revenue. Valve’s cut is simply piled on top of the publisher’s: while it would be nice to think that Majesco, Atari and company would eat the cost of distribution themselves, what with manufacturing and physical distribution out of the picture, their financially-oriented motivations strongly suggest that the proportions are the same (or worse!) than at retail.

It isn’t much better on the consumer’s side, where it can’t be missed that prices are at near-retail levels in order for the publishers to stay on good terms with their still-vital retail partners.

There’s not much that can be done about this. Even the most eager of mainstream publishers still has a massive administrative beer belly to shift before they can really start to get to grips with digital distribution, and their much smaller, perhaps even humiliatingly so, role within it.

Don’t get the wrong message: despite the gloom, this categorically does not mean that publisher contracts are Bad Things. It goes without saying that awareness of the games in question rockets, and the developers are still getting their funds; the contracts are also the only way that most studios, already locked into the publisher ecosystem, can hope to get onboard digital distribution. But as we have seen, their long-term usefulness is questionable for the developers, Valve, and in the context of digital distribution even the publishers themselves.

Motivations

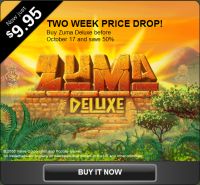

All that aside, what exactly has led Valve to publisher contracts? Rag Doll Kung Fu was described as the epitome of Steam’s independent aspirations, but it is hard to make the same claim of Bloodrayne 2 and Zuma Deluxe. The easiest answer is the love of money, but, as regular readers will be unsurprised to hear, if we look hard enough there is a more subtle (and as such more Valve-like) rationale awaiting discovery.

Consider Ubisoft, who have entered contract to distribute Dark Messiah of Might & Magic. Ubi love digital distribution. Usually headed by Beyond Good & Evil, their back catalogue games are to be found on many schemes, in fact almost every one going–and yet their Steam contract shows no indication of extending beyond Dark Messiah. With its links to Valve it is obvious why Dark Messiah is an exception, but an exception to what? Why this discrepancy at a time of such expansion?

That Valve only accept contracts from publishers need of financial support is the answer running quietly under the surface. It simply isn’t credible to suggest that only Atari, Strategy First and Majesco have ever broached the distribution issue, even factoring in possible conflicts of interest with Valve being a prominent developer. PopCap remain an anomaly, I will admit, and are quite possibly the moneyspinner they first appear.

Accepting mass-distribution deals only from those truly in need of them presents a far more positive image to the public than that of a sell-out, the other motivation visible with our current knowledge. Today’s publisher contracts might be a compromise of Steam’s initial vision but are arguably ones worth living with, at the very least until more developers become independent. It is only unfortunate that Valve cannot advertise their reasoning (if it is indeed as I’ve theorised) without embarrassing their clients.